sabine

Reviews in Danish here and in and in English here

FOREWORD BY FILL THRANE

Travelling in Greenland can be a humbling experience. That, at least, is the impression one gets reading Knud Rasmussen’s introduction to the account of the first Thule expedition in 1912: Many of the joys and experiences the travelling man finds worthy of writing down may be found naive and insignificant by the more blasé city dweller, but I have not sought to disguise this by feigning a sense of superiority I do not possess. It is my belief that total abandonment is the result of openness to the moment. As the words imply, this vast country, with its coldness, wide open spaces and hardy population needs no dramatic staging in order to communicate with its audience. Greenland is best spoken about in a low voice. It is large enough in itself.

This attitude is echoed in the work of the 23 year old Dane, Jacob Aue Sobol, travelling to East Greenland at the beginning of the new millennium. Neither his images nor his words shout. Even though his camera captures violent images there is no showing off. The intensity of the images emerges from the unspoken, the ambivalent, the understated. Sobol originally set out to take photographs in Tiniteqilaaq. Even the name of the place implies the ends of the earth: The strait that runs dry at low tide. After five weeks he had had enough. He took his black and white photographs and headed home — albeit with the sense that his village portrait was distorted. Four months later he returned to face the small society that had far more layers and levels of meaning than he had seen at first.

And that is when Greenland captures him. The mountain landscape lies transparent and luminous, and the frozen waters lure him. He makes friends among the hunters, who take it upon themselves to train him. When this new existence suddenly starts to function — despite the arctic cold he can provide himself with food — the pampered motherland to the south shrinks into the pallid past and he resolves to test his strength against East Greenland‘s basic, existential challenges. But behind this decision lies his true motivation: Falling in love with Sabine.

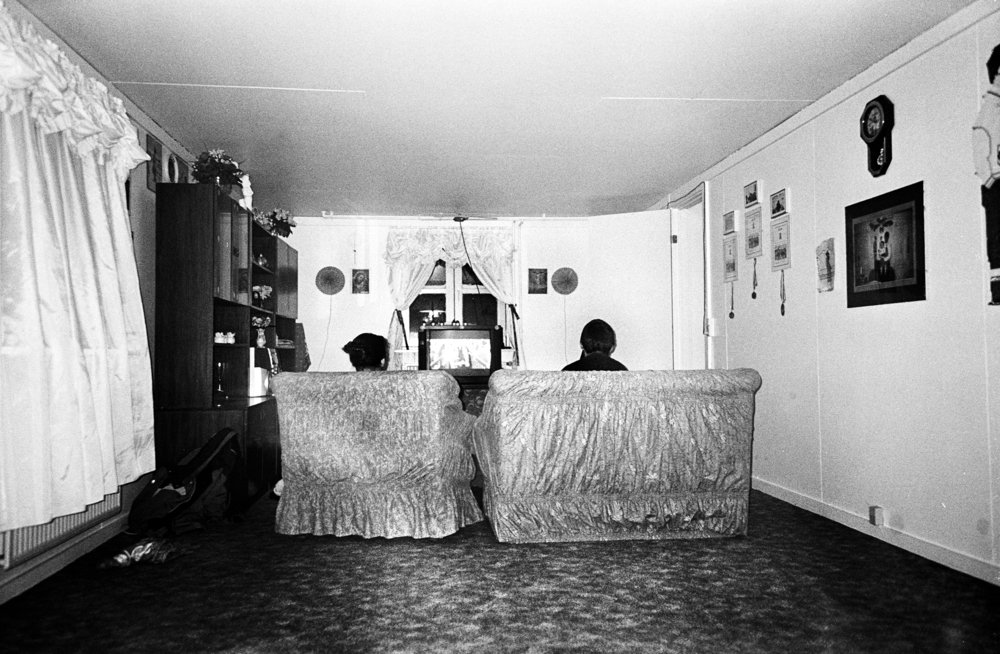

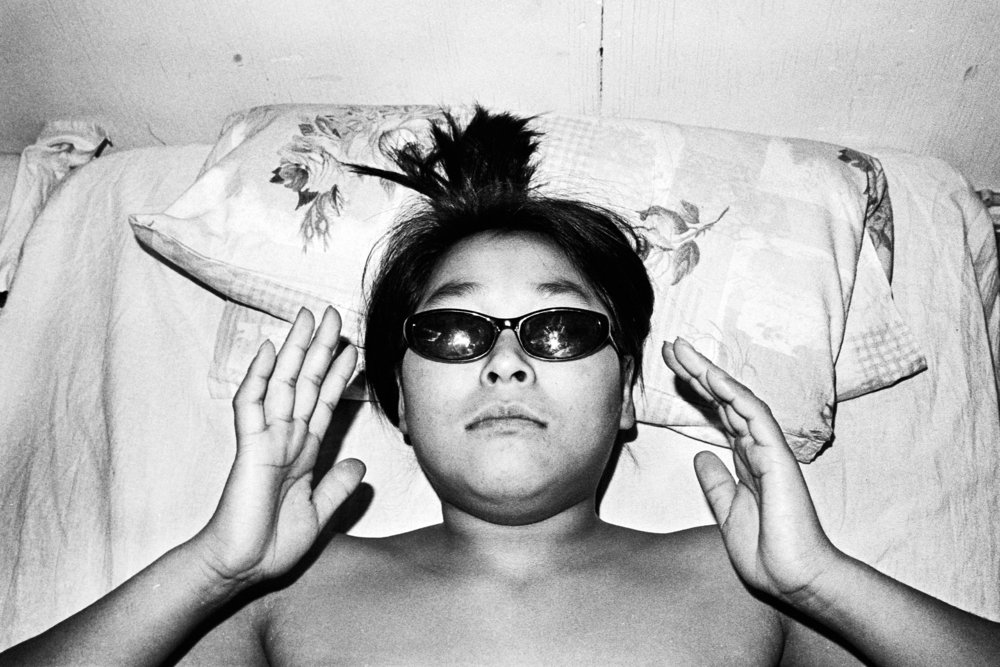

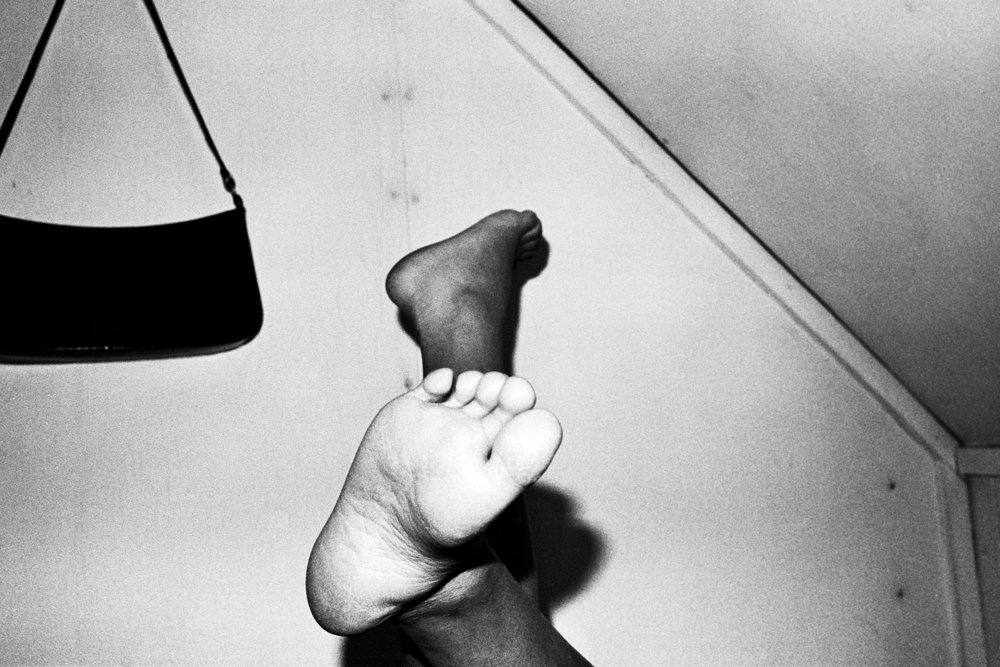

The cover photograph leads with the love theme. Through the small heart—shaped window of her fingers the main character sends a signal to the photographer who, his hands in the same position, snaps his rectangular counter signal — a picture that frames and captures everything. The game begins. The diary excerpts provide us with glimpses of his self appointed education — as the provider to be at the sealing net, as the fisherman on the ice, as the ‘husband’ in the shower — and dig deeper into his growing self realisation through notes on cultural clashes, chapters on the Piteraq storm, or close encounters with death. The photographs are less fragmentary, structurally linked through a series of ’exterior‘ pictures wrapped around a sequence of ‘interior’ pictures, more often than not with Sabine as their subject and focus. Yet concentrated glimpses (like the split seal on the bathroom floor) also link nature and the struggle for survival with a steaming eroticism. The pelting ice storms that alternate with the silence of the arctic darkness surrounding the house imply an unpredictability mirrored in Sabine’s changing expressions — passionate, arch, childishly unselfconscious, demoniacal, tender, headstrong, jealous, cool, devastated. The camera strikes like the erratic shifts in temperature indoors and out. The outcome is uncertain. We stand, sit and lie with the photographer, wondering at the chaos, the riddle of lines. Two central images depart from this series: An interior shot meeting the direct gaze of a group of happy Greenlanders — classical pre-colonial openness were it not for the girl in the centre shutting us out with her folded arms and the confrontational look on her unsmiling face. And an exterior bird’s eye view of a large group of villagers gathered as a community at a funeral. Both images depict the solidarity village life demands and depends upon, whilst leaving a crack open for a contradictory gaze: The gaze that registers the man with the camera eye, the outsider, the Dane.

For as it gradually emerges goodwill is not enough. Not even love can bridge the gap when the abyss is as bottomless as that between two cultures in disintegration and crisis. Sabine’s small, passionate heart-shaped window on the cover is captured and reflected in Jacob’s photographic rectangle. Here the denouement is established: The ups and downs of love delineate the story and are — presumably — abandoned on the last page. Is it the sensitive artist that gives shape and meaning to life through his work, or is it the woman, life and destiny that hews the man and makes him an artist? Or is it just the inescapable: The strait that runs dry at low tide?

Finn Thrane

Director, Museet for Fotokunst, Odense, Denmark